John Locke was a physician in 17th and 18th century England. His skills as a philosopher dwarfed his medical ones. Many predecessors championed rights before Locke, but Locke codified the theory and gave the world a categorization schema in his Second Treatise of Government. According to Locke, our rights are to life, liberty, and property.

You may wonder what happened to the right to the pursuit of happiness. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke discussed this idea and openly mocked it. According to him, human beings should not pursue their own happiness if that comes at the expense of God’s plan for us. Thomas Jefferson, undoubtedly aware of Locke’s works, including An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, discarded the notion that we shouldn’t have the right to pursue happiness and embraced it as one of his three broad categories of rights – life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

You probably noticed that Jefferson excluded the right to property. Did he not believe in a right to property? When a friend asked Jefferson this question, he replied that the right to property was obviously true, so there was no reason to repeat it in the Declaration of Independence. Fair enough, though not listing it had the negative consequence that many Americans disregard it today.

So, Jefferson and Locke agree on the rights to life, liberty, and property and apparently also on the rule of three. However, Locke based his dismissal of the right to pursue happiness on the oppression of religious doctrine, which is at odds with the right to liberty (i.e., the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority). To keep Lockean theory consistent (even if he couldn’t), we can safely disregard the rejection and include the right to pursue happiness.

So, we arrive at rights to life, liberty, property, and the pursuit of happiness. Yet, there’s now a redundancy in our list. If you have the right to pursue happiness, that right can only be maintained if you are not at the mercy of oppressive restrictions. If we accept the right to pursue happiness, we also have the right to liberty. Therefore, we can follow the rule of three and say that we have rights to:

Life

Property

Pursuit of Happiness

Locke and Jefferson weren’t the only authors to categorize rights. The two most famous examples are Jean-Jacque Rousseau’s categories of life, liberty, and fraternity and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, commissioned by the United Nations and championed by Eleanor Roosevelt. First, let’s consider the idea that men have the right to fraternity. Fraternity is a sense of brotherhood. To claim a right to fraternity is a contradiction of the right to pursue happiness. Suppose one person’s choice is to not enter into a fraternal relationship with another person that contradicts someone else’s rights if that person does want the same. Should some authority force the declining person to enter into that relationship?

If so, it would be a violation of the right to liberty. Rousseau’s categories are therefore self-contradictory, and we can dismiss the idea of a right to fraternity.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a more admirable system than Rousseau’s. In one respect, it’s superior to either Locke’s or Jefferson’s with its Article 2, declaring that, “Rights are universal to all human beings regardless of race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” We can and should condemn Jefferson’s use of the term “men” in the preamble to the Declaration of Independence and his lifelong claim to own people as property, especially based on their race. Locke had a more enlightened view on women for the time but did not ascribe a complete set of rights to women. Locke also got mixed up with writings justifying slavery in his government position covering the Carolinian colonies. Though he spoke out against slavery, we should look with skepticism about his purity on ascribing equality based on race. The UDHR Article 2 ought to be part of any serious system of rights (though updated to include any category of gender identity).

Where the UDHR is less helpful is with the number of rights. The list is mostly correct, but it’s too extensive. Categories are a means of simplifying a system, thus making it easier to understand and accept. Most of the UDHR are mere derivations of the rights to life/body, property, and the pursuit of happiness. Instead of establishing categories and allowing reasoning to dictate the specifics, the UDHR attempts to list everything it can. Still, it is nearly impossible to dictate all instances of rights. You have the right to exchange money with a willing merchant for a banana, apple, peach, pear, bunch of bananas, etc. When do you tell me to stop, that you catch my meaning? This argument is not to criticize the UDHR for attempting to do so. As a document meant to spell out rights to the world (including the most power-hungry dictators), it makes sense to try and be exhaustive. In our individual capacities to convince other individuals, keeping the message simple has greater utility.

The other problem is that the UHDR lists a couple of questionable items that enable proactive governments to use force. For example, the right to employment in Article 23 includes the right not to be unemployed. Let’s say that Jay has taken several jobs and, on average, has shown up when scheduled about 25% of the time, is rude to customers, and puts his feet up, expecting his co-workers to do the work for him. He’s kept one job for a record two weeks. Does Jay have a right to employment? According to the UDHR, he does, and they will either force someone to take him or give him a government job. Section 3 of the article guarantees Jay decent enumeration to provide for himself and his family. Where is the incentive to work hard if a government job awaits you as a failsafe? Any government adopting the UHDR would eventually collapse. We can safely reject the articles specifying rights that don’t derive from our combination of Locke’s and Jefferson’s categories and accept the ones that do plus the universality of rights for all people.

So, what does each of these categories of rights entail? Let’s explore them below.

Right to Life and Body

Stating there is a “right to life” unfortunately got tied up in a political movement. Let’s leave that political argument to the side and focus on the right as Locke and Jefferson meant it. Declaring that someone has a right is to claim that individual owns something and, by its very nature, is theirs to keep. Your life is yours from the day you’re born, and the umbilical cord to your mother was severed. No one can take your life from you without violating natural law once you’re born. However, Locke clarifies in the Second Treatise of Government that life also means your body, the system of organs, tissues, and cells that sustain your life. These rights are yours at birth. Anyone who disrupts or attempts to disrupt your body’s working order violates your right to life. Any physical harm done intentionally to anyone who has been born should be considered a right violation (unless in the process of stopping a perpetrator from committing a rights violation against a child or non-consenting adult).

Right to Property

In the process of living life, we acquire property, which we do through voluntary transfer from someone who rightfully owned the property or through earning it in the course of our labor. Since the origins of all property are through the labor of our bodies and we own our bodies, we also own the product of our bodies and may therefore choose to transfer that ownership to another. Whether that exchange is for some other property that we would like to have or as a gift, it is your right to dispose of your property in whatever way you choose. Again, property rights are contingent on the assumption that the means of earning or transferring the property does not involve the violation of another’s rights. For example, you do not have the right to earn your property through a contracted murder nor dispose of it on a contracted murder.

Property rights violations are typically not as harmful as a violation of the right to life and body but can be. Locke gives the example of a traveler taking a long, winter’s journey on horseback to his home. If a thief accosts him and takes his coat and horse, this act is nearly certain to kill the man, and he’s therefore justified to take lethal action if that’s the only way to prevent the robbery. Property is often a tool to support our bodily functions and, if not that, to support our pursuit of happiness.

Right to the Pursuit of Happiness

I never understood why Locke rejected the right to pursue happiness. Locke calls individual rights “natural rights” because the rights are what humans had before society formed to take human beings out of a state of nature. By that framing, pre-society humans would also have had the right to pursue what made them happy. We should be grateful to Jefferson for bringing this right back into the categories of rights.

Happiness is a state of contentment and joy. Without it, life would be unbearable drudgery at best and constant suffering at worst. Happiness brings meaning to our lives and differentiates us from everyone else. A complete accounting of what makes an individual happy is singularly unique. I’m happy when I spend time with my daughters, sing karaoke, write fiction, and ride roller coasters, among many other activities. How does that sound to you? Did all four of those activities describe what makes you happy?

We need this right because of all the billions of people in the world; you are the only one who has access to your mind, feels everything you feel, thinks everything you think, does everything you do, and believes everything you believe. And so, no one can know what makes you happy unless you reveal it. We use our bodies and property to pursue happiness; therefore, our pursuit of happiness is also ours, and thus we have a right to it (again, as long as our pursuit of it doesn’t deny another person’s rights).

Conclusion

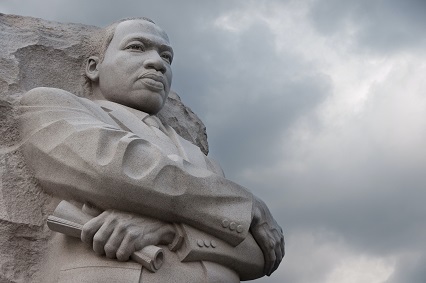

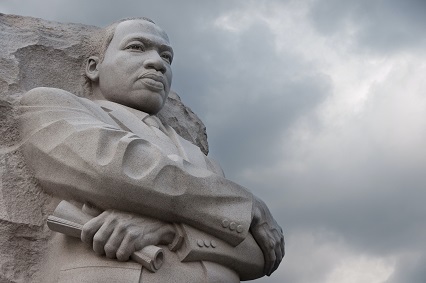

Those who don’t deny the rights of others are entitled to enjoy them. Even those who do violate others’ rights are entitled to a fair punishment that acts as a deterrent to future crime with no cruelty or completely unprecedented acts inflicted against them. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once explained, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Rights theory gives us a framework for recognizing injustice. Uprooting it when and where it happens is the key to making the world a fairer, more loving, and happier place to live.

Home | Rights Theory | Love | Toxic Personalities | Fiction | Charlton’s Ground | About Me

Red Flags | Motivations | Fears | Techniques | Inabilities | Stages | Enabling | Defenses Against